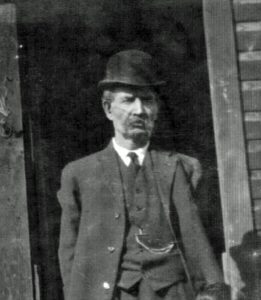

McPHAIL, Archibald (1850-1923)

Archibald “Archie” McPhail

Mining Engineer

Archie McPhail in Calgary

Born: 20 Oct 1850 at Schooner Pond, Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia, Canada

Married: 25 Sept 1874 at Caledonia, Nova Scotia to Agnes Roe Cameron

Died:25 May 1923 (age72) at Calgary, Alberta

Buried: Union Cemetery, Calgary, Alberta, plot K:04:005

Family Tree: Archibald McPhail in Family Genes

Contributor: Jim Benedict

Archie’s Parents

- Father: Alexander McPhail

- Mother: Annie McRae

The Early Years

Archibald was born in Schooner Pond on north Cape Breton Island, N.S. His father came from Androssan, Scotland. His mother’s family, headed by Donald McRae, lived next door.1 The area was known for rich coal seams underground and the hardworking Scottish families were most welcome.

His father, Alexander, was able to acquire property in the Schooner Pond area; 100 acres and then 80 acres.2

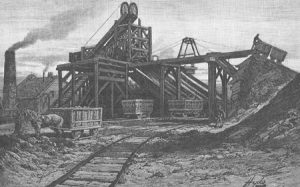

Archie and Agnes McPhail

Caledonia coal mine in Nova Scotia 1882

Agnes Roe Cameron was born on December 30, 1856, of John and Ann Cameron; he born in Nova Scotia and she in Scotland3 Her father was a blacksmith, which would have been useful in the coalmining area of Lingan Mines in Cape Breton. Archie and Agnes were married at Caledonia, Cape Breton, Nova Scotia when he was 24 and she was 18.4

Archie was a mining engineer and likely worked for Lingan Mines in Caledonia. By 1901, the family had grown with six children at home. The two older boys had left home and the next two were working, William as an engineer, young Archie as a blacksmith.

In March of 1902, Agnes purchased a sewing machine in Glace Bay, for 38 dollars. A luxury at the time, but vey useful in a large family. In a few months, the family uproots for traveling west, out to Frank, N.W.T. in the Crowsnest Pass area, some five thousand kilometers away from home. The West was opening up and the CPR Railway needed coal for their steam locomotive

The Children

- Alexander McPhail

- John McPhail

- William McPhail

- James Henry McPhail

- Archibald “Archie” McPhail

- Anna “Annie” McPhail

- Agnes Roe McPhail

- Stanley McPhail

- Catherine “Katie” McPhail

- Mary McPhail

- Gordon McPhail

- Mildred McPhail

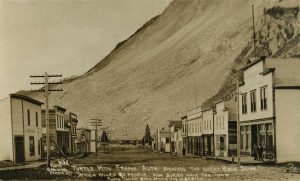

The Frank Slide

Frank, Alberta after the slide 1903

0n a cold, bleak morning — the 29th of April, 1903, the little town of Frank slept peacefully in the shadow of a great mass of rock known as Turtle Mountain, a peak which was to be known as the most menacing in the Rockies. In certain tiny homes, women and children were alone, for part of the male population of the town were on night shift in the mine, far under the mountain.

Some say that the peak was named Turtle because it moved slowly. Others vow that it was on account of the rounded, bulky shape somewhat like the back of a turtle. Be that as it may, on this cold grey morning, at ten minutes after four, this giant mound rose from its inertia of untold ages, shook its huge head and sent thousands of tons of rock hurtling down upon the tiny town, sleeping so peacefully below. No warning, chance of escape as the whole northeast face of the mountain collapsed, moving in a terrific, thundering avalanche across the beautiful valley, carrying ahead of it, or cruelly crushing beneath, dozens of homes, and rushing into eternity, without a moment’s warning, some 65 helpless souls.

Just before giant, unseen forces had hurled down this avalanche, a C.P.R. freight train had passed through the town of Frank and was scarcely beyond the danger zone, when a sound that the crew will never forget, filled the air above the noise of the train. With incredulous stupefaction, they gazed at the fearful scene behind them — a sea of great, jagged rocks over which hung a thick grey veil that might have been a funeral shroud, so many bodies did it cover.

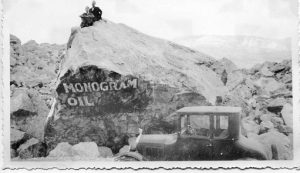

Jack and Albert Benedict on slide boulder

As the dust was slowly settling over this great mausoleum, dozens of miners — husbands, fathers and brothers — were preparing to emerge from the entrance of the mine, when they suddenly found the way blocked. The fact did not cause any great surprise, since, for several months past, the timbers in the mine had been occasionally broken, especially about the entrance. This was evidently a small cave-in. It was a simple matter to retrace their steps and emerge from a more westerly exit. The dawn of a new day cast its early morning light on a sight that struck terror to their hearts. Before their astonished and unbelieving eyes there was nothing but a great, weird expanse of rock. It was as If some cruel wizard had suddenly swept their tiny homes and families into oblivion, and left in their place, this strange, fearful world of grey.

Among the residents of Blairmore, who vividly recall the slide of Turtle Mountain, is “Cap” Beebe, one of the oldest and best known persons in the Pass. “I remember it as if it happened yesterday,” he said. “I was awakened between three and four o’clock by a most terrific noise and vibration that I believed to have been thunder. I lay still waiting for further crashes and for the sound of rainfall but none came and I went back to sleep.

“About five in the morning I was wakened by a loud pounding on my door and found Felix Montibetti there, greatly excited.

“It’s gone,’ gasped Felix.

“What’s gone?” I asked in perplexity.

“The town of Frank.”

“The town of Frank,” I repeated slowly as if trying to analyze his words. “Was there an explosion? Do you mean that it was blown up?”

“No,” he answered fearfully. “The mountain fell on it.”

“That was the terrible rumble of thunder that I had heard. After quickly dressing, I joined him and we hurried down to Frank — and what a sight! I shall never forget it. Rocks were still rumbling and falling down the sides of the mountain and continued to do so for days. There was no such thing as relatives searching for their families — they were buried beyond recovery.”

The noise of the fall was heard even in Cowley and many thought that there had been a mine explosion.

Along the route of the old highway, the large rocks were utilized as an advertising medium, but at present there are restrictions in regards to such things, which is as it should be in this particular place, for the whole slide is really the burial ground for the many bodies that lie there.

Mr. and Mrs. Sam Ennes and their four children lived in Frank, along the same row of houses as a family by the name of Leitch. Both families were fast asleep, as were the other residents of Frank, when suddenly the thousands of tons of rock came tumbling down the mountain sides to crush, like matchwood, the frail houses below.

Down the same row, a number of houses beyond the Ennes home, lived the Leitch family. Mr. Lietch was a Scotchman and kept one of the general stores in Frank. Fate was not so kind to his family, for their home was crushed into oblivion but on a rock that was pushed far along, to a window of the Banister home, lay a little baby, the youngest member of the Leitch family. The child, Marion Lietch, later became Mrs. Lawrence McPhail and lives in Nelson, B.C.

- from Calgary Herald, March 27, 1937, by Freda Graham Bundy

17 Miners Survive

It was 4:10 am on the early morning of April 29, 1903. The miners had gone up to the mine tipple and entrance; three stayed topside and 17 descended into the workings. Only the 17 would survive. A terrible rumble raced through the tunnel, alerting the men. Thinking it might have been a gas explosion, they ran to the mine entrance, only to find a jumble of fallen timbers and massive rocks, blocking at least three hundred feet of tunnel to the opening. They were trapped.

As the air quieted, the men took stock of their perilous situation. The exit was totally blocked and water was rising. Likely their air shafts were also blocked. Explosive gasses could be pooling in pockets. But, being miners with tools, they started to dig out. It was obvious that the mine entrance could not be reached, one man said there was a diggable seam of coal further back, that might reach up to the surface.

The men found the seam and started to dig for their lives, working in relays of two or three at a time. Finally, over 12 hours later, a pick broke the remaining overhead rubble and daylight and fresh air streamed down on the men. Dan McKenzie stepped out first and stared down at the disaster below, rocks strewn across the valley and up the far hillside. Fifty yards below, a small knot of men were trying to dig around, looking for the hidden mine entrance. A whoop from Dan alerted the crew and there was a joyous yelp of relief back.

All the entrapped miners escaped. Some lost their homes. Some lost their entire families to the slide. One miner, 28-year old Alex McPhail, returned to his family below and joined them in relocating to Calgary. He became a stationary engineer for Templeton’s Ltd., for 18 years and passed away in 1947. Alex is buried with his family in Burnsland Cemetery.

Move to Calgary

McPhail house in Calgary

After the Frank Slide disaster, there was no more mining work available in the area. Likely Archie and Agnes had enough of the rough and dangerous coal mining work and sought a better life for their children. They first settled in a bungalow at at 323 Eleventh Avenue East in Calgary. The McPhail family’s last residence was at 108 Seventh Avenue NW, pictured here.

Later Years for Archie

Archie ended up working for CPR at the Ogden shops as a machinist for many years. In 1918 he retired in good health. He passed away in 1923.

- Canada Census of 1861 for Nova Scotia [↩]

- Schooner Pond land grant map – undated [↩]

- Canada Census of 1871 for Nova Scotia, Cape Breton, Lingan Mines District [↩]

- Marriage register [↩]